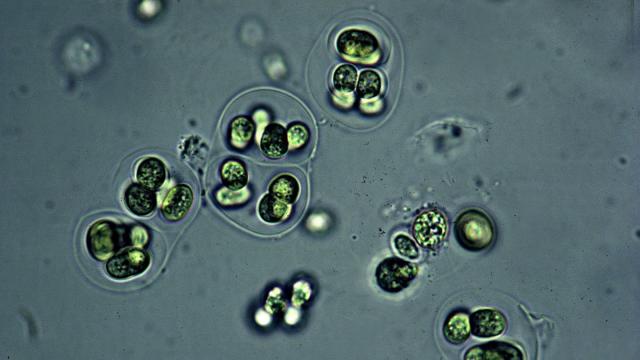

The earliest direct evidence of photosynthesis has been unearthed in fossils dating back 1.75 billion years. Researchers collected fossils from Australia, Canada, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, discovering traces of cyanobacteria in the Australian and Canadian samples. Cyanobacteria, Earth's oldest known lifeform, is believed to have originated 2 to 3 billion years ago, evolving to perform oxygenic photosynthesis.

A study published on Jan. 3 in the journal Nature unveiled cyanobacteria fossils with photosynthetic structures, specifically thylakoid membranes containing pigments like chlorophyll. These pigments convert light into chemical energy through photosynthesis. Preserved in mud clay that transformed into rock over time, the cyanobacteria were meticulously examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to reveal tiny details, including the membranes.

Rather than employing light for imaging objects, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) utilizes electrons, which possess a significantly smaller wavelength than light. This characteristic enables the observation of finer details down to the atomic level. Scientists expose a sample to an electron beam, where some electrons pass through, while others are either absorbed or scattered by denser portions of the object.

Lead author Emmanuelle Javaux, a paleobiologist from the University of Liege in Belgium, explained to Live Science, "The discovery of these membranes confirms that the cells in question are indeed cyanobacteria engaged in oxygenic photosynthesis." She added, "This revelation extends the fossil record of such membranes by 1.2 billion years."

Javaux emphasized that pinpointing the specific period when cyanobacteria developed the capacity for oxygen production marks a crucial milestone in Earth's natural history.

The microfossil, credited to Emmanuelle Javaux, serves as evidence of photosynthesis occurring 1.75 billion years ago.

Approximately 2.45 billion years ago, during the Great Oxidation Event, there was a significant surge in atmospheric oxygen levels, reshaping life on Earth. This increase facilitated aerobic respiration for various organisms and accelerated mineral weathering, contributing nutrients to diverse environments.

Despite this knowledge, the triggers behind the Great Oxidation Event remain a topic of debate among scientists. The exact interplay of ecological and geological events leading to this event is uncertain. While cyanobacterial photosynthesis is widely accepted as a primary factor in the rise of oxygen concentrations, alternate drivers such as volcanic eruptions or reduced oceanic iron levels are considered.

Greg Fournier, a geobiologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, emphasized the ongoing debate, stating, "If oxygenic photosynthesis evolved very early, but atmospheric oxygen accumulated later, other processes like the burial of organic carbon may have been at play."

The age of the fossilized structures aligns with current theories on when cyanobacteria featuring thylakoid membranes emerged. The researchers' use of electron microscopy opens the possibility of reanalyzing older fossil samples to precisely determine when cyanobacteria first evolved thylakoid membranes.